Our fifteenth bulletin considers the scale of existing shortages, and indicates some ways the new government might begin to tackle them.

Early in October, Edge researchers and East Kent Colleges Group's Suzanna Gamwell were invited to Latvia to learn about the Vocational and Technical Education system. Latvia represents an interesting comparison with nations of the UK. It is similar to Scotland in terms of land area, but less densely populated, with around 2 million people. Riga, Latvia’s capital, is home to approximately 600,000 people – tiny compared to London’s 8.8m throng. Vocational Education and Training in Latvia is part of a three-tiered system: primary, secondary, and higher education and managed by the Ministry of Education and Science. The Ministry wields considerable influence, through workforce planning and centralised job forecasting, which guides the allocation of resources and places in vocational schools in an attempt to align the output of graduates with labour market needs.

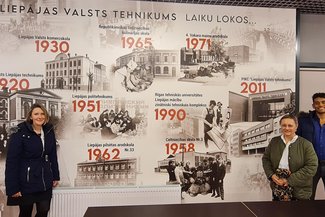

Our first visit was to Liepajas State Technical School, a vocational secondary school in a western seaside resort with around 1400 students. Their status grants them 10% more funding and allocates them responsibilities as regional leader in vocational education. This collaborative approach is reminiscent of Northern Ireland’s Curriculum Hubs. The school was particularly interested in linking subjects and new approaches to delivery. It was also proud of its employer engagement, which includes tailored programmes like a new Aircraft Mechanics programme, linked to international standards, developed in partnership with airBaltic.

Next day we headed north to Venspils University of Applied Science and Ventspils Technical School. The University is a small, applied institution with specialisms in radiography, electrical engineering, economics, and translation studies. Its small size, with around 700 students, facilitates close relationships with local employers. The majority of students end up employed in the region while many of the university’s faculty members also come from industry. Ventspils Vocational Technical School, with 800 students, provides a broad vocational curriculum. The school has been proactive in securing EU funding, particularly through Erasmus+ projects, which have allowed it to innovate in areas like energy transition skills. . This emphasis on green skills aligns with broader European trends.

Our final visit was to Bulduru Technical School just outside Riga, which specialises in agriculture and catering. We were struck by the school's innovative use of its greenhouses, which provide a learning resource, but also generate income through the sale of produce. The school's collaboration with universities and its use of technological innovation is showcased in its labs and, most strikingly, by a robot designed to monitor plant growth. Our visit ended with a visit to the Ministry in Riga for discussions with the places we visited, which provided an opportunity to reflect on our experiences.

The immediate challenges facing Latvian vocational education and training providers are financial and governmental. Latvia’s centralised approach to workforce planning and vocational education contrasts with the more decentralised systems in the UK, particularly in England. But there is growing interest in a more flexible approach through stewardship of the skills system informed by labour market forecasting, through Skills England and in Wales through Medr. In Latvia, student places are allocated based on forecasts like these, but some institutions expressed frustration with the rigidity of this centralised model, because it can fail to capture local granularity and specific workforce demands.

In the Latvian funding regime, as in the UK, funding has been eroded by inflation. We heard, astonishingly, that the level of funding per student had not risen since 2007. In this severely constrained situation, attracting external funding, and particularly EU capital funding, was particularly important. This was what paid for much of the excellent learning facilities we saw.

The legacy of the Soviet era still casts a long shadow over the country, especially in light of the outbreak of the Ukrainian war. Interest in participating in Europe is driven in part by desire for independence of language and culture. In stark contrast to provision in the UK, language competencies were far more prevalent across the institutions we visited. General curriculum in schools included Maths, Latvian, and English. The schools also sustained a strong interest in national arts and culture. Following independence, Latvia implemented policies to promote the Latvian language and reduce the dominance of Russian in public life, including education. This has led to challenges for Russian-speaking students though, who often require additional support - integration of Russian-speaking minorities was a recurring theme.

Suzanna Gamwell, Group Head of Business Innovation at East Kent Colleges Group"A key takeaway for me was the technical schools’ focus on innovative project work, the creativity and drive of project teams and the strong support from senior leaders…It was also useful to consider the advantages created by schools coordinating around curriculum development and resource-sharing, which not only created efficiencies for the curriculum teams, but also gave schools greater leverage when engaging with big employers."